Unholy gatherings, conical hats, ritual sacrifice, consorting with demons — to anyone familiar with depictions of witches in the medieval and early modern eras, these themes will be quite familiar.

And yet, how much do we really know about where these depictions originated? Why did people believe witches wore pointed hats? Why were they accused of kidnapping and eating children?

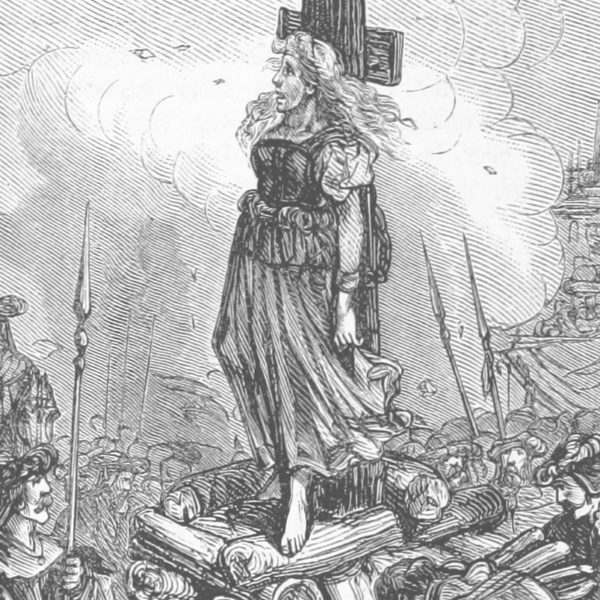

As the number of practicing witches around the world continues to climb, interest in learning about the witch trials — often known as the Burning Times — has grown, too.

There are stories shared of the fierce women who spoke out against economic and land inequality, and who were in turn silenced forever by those in power.

There are stories of the herbalists and healers — those who kept remnants of the old ways alive through their practices, whose lights were snuffed out by fearful and greedy men.

There are stories of those who claimed their wild powers at the very end, using their dying breath to curse those who sentenced them to death.

These are all important stories worth telling.

But one story we don’t often hear being told is that of the deeply rooted link between the witch trials and antisemitism.

“Indeed, many early modern stereotypes about how witches looked and behaved were rooted in a long history of antisemitism. Before the Church turned its attention to witches, heretics and Jews were its primary targets.” — Celeste Larsen, Heal the Witch Wound

Overlapping Stereotypes

Many of the stereotypes that were used to slander and vilify accused witches during the Burning Times can be traced back well before that period in history — and back then, they were used to cause harm to a different population: Jews.

Like witches, Jews were regarded as antagonistic, misanthropic “others” who defied all that it meant to be a good Christian — attending church on Sundays, respecting and partaking in the holy communion, adhering to Church rules and regulations.

Like witches, Jews were used as scapegoats for various tragedies and disasters. While witches were accused of using magic to summon hailstorms and plagues, Jews were accused of using mundane means such as poison (though sometimes magic, too) to cause illness.1

Like witches, Jews were accused of consorting with Satan and participating in the ritual murder of children, usually known as “blood libel” in this context.

Like witches, Jews were depicted in artworks of the era with certain stereotypical features: large hooked noses, pointed hats, and devil-like features (or existing in the company of various devils).

And it feels important to note that this discrimination and violence occurred against Jews first, well before the peak of the witch trials began.

A Brief History of Medieval Antisemitism

Antisemitism has ancient roots; the earliest recorded instances can be traced back to ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome.2

But the persecution of Jews in Europe rose to horrific extremes during the Middle Ages, reaching an initial peak during the Crusades and a second peak during the Black Plague epidemic during the 1300s.

In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council established a number of laws outlining the manner in which Jews must identify themselves (primarily to ensure an unsuspecting Christian would not sleep with or marry them, but also to facilitate easier barring of Jews from guilds and jobs).

Among these was the Judenhut, or Jewish hat — a cone-shaped hat with a circular brim. This is one (though not the only) theory regarding the origins of the stereotypical pointed witch’s hat.

Throughout the Middle Ages, hundreds of Jewish communities were damaged or destroyed as Jews were banished, forced to convert, and killed — often by burning. These massacres were especially concentrated in the regions that now make up modern-day Germany — a theme that would be reflected later during the witch trials as well.

The supposed crime that warranted such a cruel and violent punishment? In many instances, blood libel — the consumption of Christian blood (usually that of children) in a twisted perversion of the Eucharist, or the holy communion.

In other instances, Jews were falsely accused of desecrating the host (the Eucharist wafer) — a crime viewed as similarly blasphemous. This was often believed to occur during the Jewish Shabbat.

“Furthermore, because the Jewish Shabbat or Sabbath was a non-Christian ritualistic gathering, it was viewed as heretical, satanic, and depraved. Jews were accused of desecrating the host, sacrificing children, and fornicating with the Devil at these gatherings.” — Celeste Larsen, Heal the Witch Wound

These vile accusations stemmed from the belief that Jews had “putrid” or polluted blood as a result of their Saturnine natures, which causes them to crave “pure” Christian blood.3

Some people believed that partaking in blood libel granted certain evil powers, which could be used to summon demons and cause harm to others.

What does all of this history have to do with the witch trials?

Though we often hear tales of accused witches summoning storms, cursing neighbors, and flying through the night skies, in truth, the desecration of the Eucharist was one of the most common crimes that suspected witches were believed to have committed.

Additionally, many witches were accused of kidnapping and eating children — a perversion of the work of midwives and herbalists who sometimes aided in abortions, but also a new retelling of the malicious lies told about Jews during the Middle Ages.

Many of these overlapping stereotypes of Jews and witches are referenced in Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum (1486), also known as the Hammer of the Witches. In fact, the Malleus Maleficarum was based on an earlier work with a similar name: Malleus Judeorum (or Hammer of the Jews), published around 1420 by the inquisitor John of Frankfurt.

Furthermore, Heinrich Kramer has previously been involved in a trial of Jews years before publishing the Malleus Maleficarum. In his work, he writes that, “the heresy of witches is the most heinous of the three degrees of infidelity,” with that of Jews being second and of pagans being third.4

Fear & Hatred of “The Other”

While many people think of the European witch trials as occurring during the medieval era, they actually largely took place during the early modern era, reaching their peak between the 15th and 18th centuries.

This was a complex period in history with many, many threads to explore — moral panic, religious conflict, misogyny, patriarchy, capitalism, imperialism, economic inequality.

But the thread that most compellingly connects the witch trials with the historical persecution of Jews is humankind’s tendency to fear the Other — and to justify abuse of them.

While there is often a certain air of mystery invoked when we discuss the witch trials, the harsh reality is that the tens of thousands who lost their lives were simply people — innocent people who did not deserve the pain and suffering they endured.

Why were they forced to endure such suffering? Because they didn’t fit the mold that was expected of them.

Many of them were women — elderly women, divorced women, poor women, rich women, ugly women, beautiful women, powerful women, outspoken women.

Others were people without homes, people with disabilities, people who defied gender norms.

And many of them were Jewish.

All of these populations represent the “Other” — the inverse of the population in power: white, wealthy, able-bodied, heteronormative, Christian men.

As much as it is part of human nature to fear the Other, it is also part of human nature to think of ourselves as good, decent people.

How can one think of themselves as a good and decent person while so horribly mistreating other living, breathing, thinking, feeling human beings?

The solution is simpler than you might think: by rewriting them as something less-than-human.

Because Jews, women, and other populations of people who were violently massacred throughout history were regarded as inherently evil and diabolical, those responsible for inflicting that violence were eased of their shame and guilt.

While the European witch trials were the result of multiple influences that worked together over the span of hundreds of years, it is certainly safe to say that Europe’s established history of persecution and violence against Jews was one of those major influences.

And that’s a story that deserves to be told, too.

Writing about the atrocities of this period in history is never easy — even less so when it feels like I am treading the line into someone else’s story to tell.

I am not Jewish, but I am the author of a book that dives deep into the history of the witch trials and the work of healing the witch wound. In my book, I speak candidly about how healing the wounds of colonialism, capitalism, white supremacy, and religious intolerance is an important part of this work.

With antisemitism on the rise — including within the pagan community — staying silent about these topics is not an option. I welcome any feedback and critiques from the Jewish community to help me improve my sharing of this history, and I absolutely will not tolerate any form of antisemitism expressed in comments on this site or elsewhere.

Sources

1. Nico Voigtländer and Hans-Joachim Voth, “Persecution Perpetuated: The Medieval Origins of Anti-Semitic Violence in Nazi Germany,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127, iss. 3 (2012); https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjs019.

2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antisemitism#Ancient_world

3. Yvonne Owens, “The Saturnine History of Jews and Witches,” Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural 3, no. 1 (March 2014); https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/preternature.3.1.0056

4. Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger, The Malleus Maleficarum of Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger, translated with Introduction, Bibliography, and Notes by Montague Summers (New York: Dover, 1971).

Leave a Reply