As humans, our connection with the Earth is inescapable. For 200,000 years, our ancient ancestors depended on the lands in which they lived to survive and thrive. Much like the other creatures of Earth, they tuned into the cycles of nature in order to get by: the solar year, the lunar phases, animal migration patterns, the tides.

Food, water, air, shelter: all of it was necessary to survive, and all of it was a gift from the Earth. Is it any wonder that the earliest religions may have incorporated the worship of a Great Mother, perhaps the Earth herself?

The deification of the earth dates back thousands of years, and perhaps longer—though because the earliest humans did not create written records, we cannot know with certainty whether the idols and drawings they left behind in fact depicted Mother Earth, another goddess, or simply symbolized the life-birthing abilities of the female form.

Still, archeological discoveries such as the Venus of Hohle Fels (dated between 40,000 and 35,000 years ago) and other Venus figurines point to the possible worship of a prehistoric Mother Goddess who represented fertility and reproduction.

Later religious texts and cultural myths do mention Mother Earth in various forms, and by many different names. She is often the personification of both the earth and motherhood, and is commonly associated with fertility, childbirth, agriculture, cattle, forests, and mountains.

The Earliest Earth Known Goddess: Dhéǵhōm

In the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European cosmology, the sky father Dyēus was the deified daylight sky. His likely consort was Dhéǵhōm, the earth mother. Whereas Dyēus was light and associated with the heavens, Dhéǵhōm was dark and dwelled in the realm of mortals.

She was the giver of all life, and also the receiver of everything that died. Thus, Dhéǵhōm was linked with both fertility and growth, as well as decay and death.

It is important to note that these mythological motifs are not directly attested in any body of text, as the Proto-Indo-European speakers lived in the prehistoric era (literally the period before written records).

Rather, these myths have been reconstructed by scholars based on the similarities between inherited Roman, Greek, Norse, Vedic, Celtic, Baltic, and other mythologies.

10 Names for the Earth Mother Goddess

Hòutǔ is the Chinese Queen of the Earth, and the deity of deep earth and soil. In one of her myths, she saved many lives by correcting the flow of water during the Great Flood of China.

The Gaelic deity Litavis was most likely an earth goddess. Her name has been found in inscriptions in which she is invoked alongside the god Cicolluis (linked with Mars, Tîwaz, and Týr).

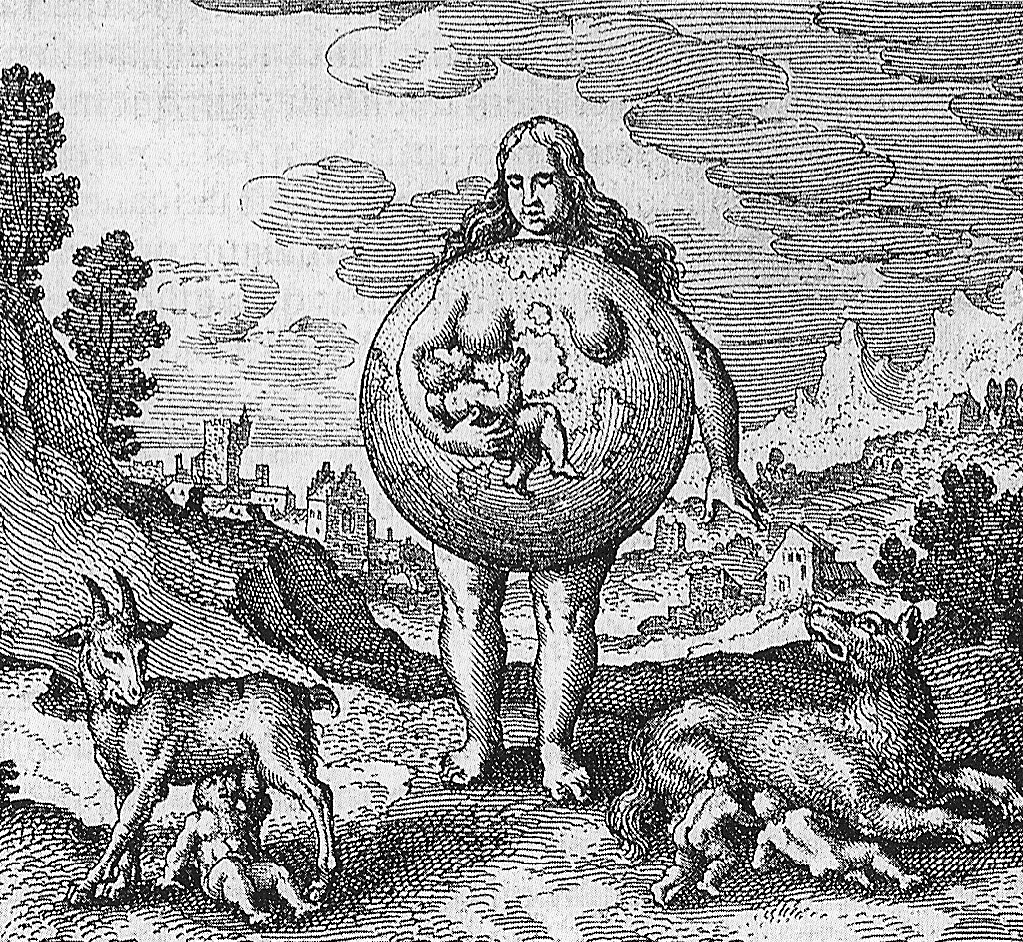

In Ancient Greek Mythology, Gaia (also spelled Gaea) was the primordial mother of all life and the personification of Earth. She birthed Ouranos (Uranus, the sky), then with him bore the Titans. She also gave birth to the sea, Pontus, from whose union she bore the primordial sea gods. Gaia was depicted in ancient artwork as matronly and “wide-bosomed,” sometimes only half-risen from the earth.

The Roman counterpart of Gaia was Terra Mater (Earth Mother). She was primarily celebrated during agricultural festivals and fertility festivals, often alongside Ceres. The Ancient Romans may have invoked Terra during certain rites of passage, such as the birth of a child.

Jörð is the personification of the earth in the Old Norse religion, and the mother of the god Thor. Her name translates literally to “land” or “earth,” and is sometimes used as a kenning (a type of figurative language popular in Old Norse writings) in skaldic poetry.

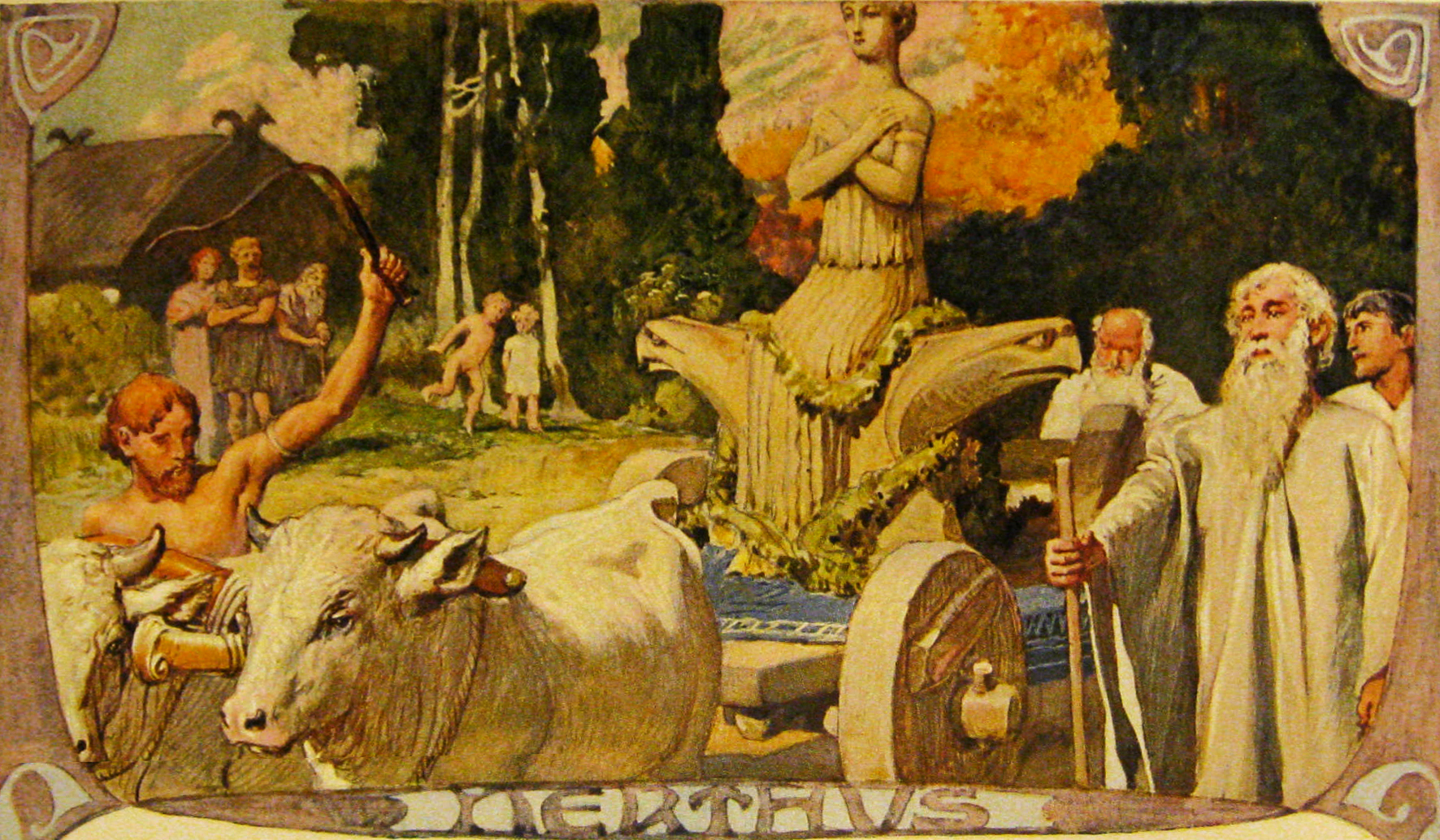

The Roman historian Tacitus likened the Germanic goddess Nerthus to Terra Mater or Mother Earth. In his book Germania, he described a ritual in which a consecrated chariot drawn by female cattle was driven from a sacred grove through the countryside, followed by days of feasting. This may have occurred on the island of Zealand in Denmark. Nerthus is usually identified as a Vanir goddess in Norse mythology.

Žemyna is the mother goddess of the polytheistic Lithuanian religion. She personifies the fertile earth, and nourishes all human, animal, and plant life. Worshippers may have sacrificed baked bread and animal bones. Her consort was either Perkūnas, the thunder god, or Praamžius, the sky god.

Among the Aztecs of Central Mexico, the name of the Sacred Mother was Tonantzin. She was also regarded as the Goddess of Sustenance, the Honored Grandmother, and the Mother of Corn.

To the Incas, the indigenous peoples of the Andes, she was Pachamama: the fertility goddess who sustains all life on earth, presides over harvests, embodies the mountains, and has the ability to cause earthquakes. According to mythology, Pachamama was the mother of the sun god and the moon goddess.

In Māori mythology, Papatūānuku was the earth mother who created the world with the sky father Ranginui. Their children, the gods, were born into a world of darkness, as Papatūānuku and Ranginui were locked in a tight embrace. The gods forced their parents apart, and to this day the sky father’s tears fall towards Papatūanuku in grief, and she sometimes shifts and stretches in an attempt to break free.

Modern pagans who venerate the Earth Mother in any of her various forms might agree with the statement that it is not the name by which we address her that is important; she is the eternal woman and the mother of all life, and those who seek her presence in their life need only ask—or more accurately, they need only to step outside into her domain and sense her presence for themselves.

Just as all life comes from the Great Mother, all life eventually returns to her as well. No matter which spiritual path you walk in this lifetime, let us all care for Mother Earth as she cares for us.

This was a fun little read, thank you. I especially enjoyed the bits about the Eastern European and PIE Earth Mothers as I didn’t know about them.