How did the Norse pagans worship their gods and goddesses? What did Old Norse sacred spaces look like? Did the Vikings build altars or shrines for religious rituals? Why are there so few Norse temples compared to other ancient cultures?

As modern pagans, these are all questions that may come to mind when setting up our own sacred spaces in our homes. For many of us, following the same traditions as our ancient ancestors may help us feel more connected to our ancestral roots and more grounded in our spiritual practices.

Unfortunately, we will likely never know the full extent of Old Norse religious practices, as very little information was recorded by the Vikings. Most of what we know comes from a combination of 1) archeological discoveries and 2) explanations of Norse pagan religious practices written down by Christians—an inherently biased source.

Still, between these sources historians and reconstructions have been able to piece together a compelling picture of what Norse pagan sacred spaces and rituals may have looked like during the Viking Age.

Table of Contents:

- Folk Religion vs. Organized Religion

- Ancient Norse Pagans Primarily Worshiped Outdoors

- Norse Pagan Temples and Indoor Sacred Spaces

- Did Norse Pagans Set Up Altars in Their Homes?

- How Can Modern Norse Pagans Create a Historically Accurate Sacred Space?

Folk Religion vs. Organized Religion

Firstly, it is important to keep in mind that the Old Norse religion was not an organized religion like the kind we know today. Norse religious worship was deeply integrated with daily life, centered primarily around survival of the family unit.

War, hunting, fishing, traveling, and farming all had their risks and dangers, and the Norse pagans turned to the gods seeking protection and good fortune in these endeavors.

Local spirits of the land (landvættir) were just as important as major deities—if not more so—and it was common for every village or family unit to have their own customs and beliefs. Land spirits often had local names, and would not be widely known despite being deeply important to the local community.

A village of fishermen who lived by a steep cliff overlooking the sea would have different risks and needs—and might therefore venerate different deities and land spirits—than a village of farmers who lived near a waterfall.

For this reason, it may be helpful to think of Norse paganism as a system of related beliefs and customs that varied based on the geography and needs of the local people, rather than a single religious doctrine.

Despite these regional and cultural variations, there are still some aspects of the Old Norse religion that can be generalized; for instance, the importance of sacred acts and ritual practice.

A simple way to explain this key importance is that Norse paganism centered around what you did, rather than what you believed. This core ideology stands in stark contrast to Christianity, which is built upon the concept of faith.

For the Vikings, it was not their belief in the gods, ancestors, and land spirits that brought them strength, protection, and good luck—it was the sacrifices, offerings, and rituals they performed.

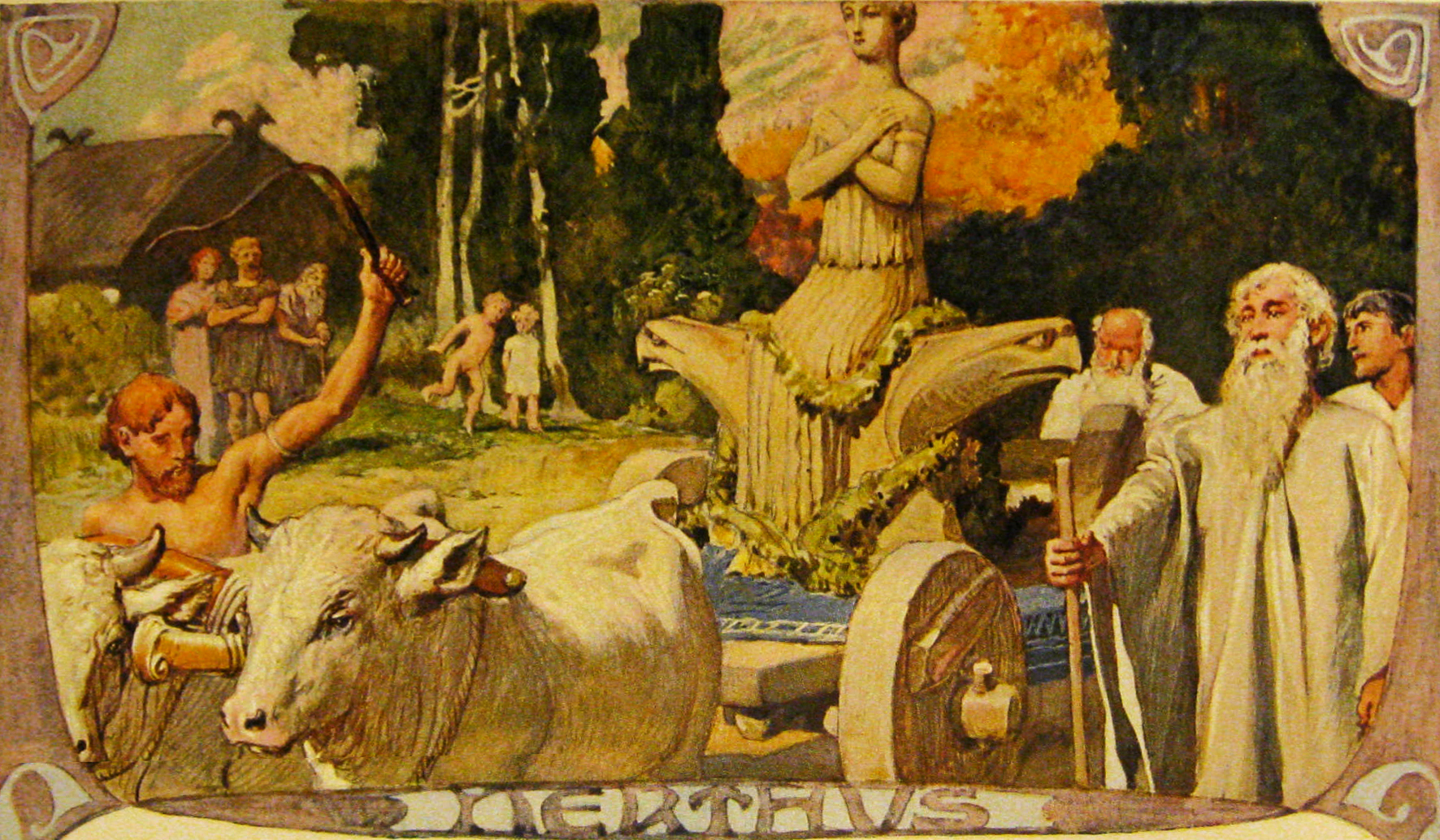

Sacrifice (blót) was the foundation of Old Norse religion. Certain blóts were held annually, such as those marking the changing of the seasons. Others were held before expeditions, duels, funerals, or other important events throughout the year. Ceremonial mead, ritual offerings, animal sacrifice, and occasional human sacrifice all played an important role in these blóts.

In concluding this section, I’d like to make another very important point: when we talk about the Ancient Norse religion, we are not just talking the religion of those peoples who lived during the Viking Age (793–1066 CE); we are also discussing the religion of the people who lived as early as the Scandinavian Iron Age, which started around 500 BCE.

That’s more than 1,500 years of religious traditions and beliefs to dissect! Naturally, the religious practices of someone living in Denmark in 500 BCE would likely differ in many ways (including the types of sacred spaces used) from that of someone living in Iceland in 900 CE, even if they both fall under the broad category of Norse paganism.

Below, I will do my best to summarize what we know about Norse pagan sacred spaces throughout history, but please keep this disclaimer in mind.

Ancient Norse Pagans Primarily Worshiped Outdoors

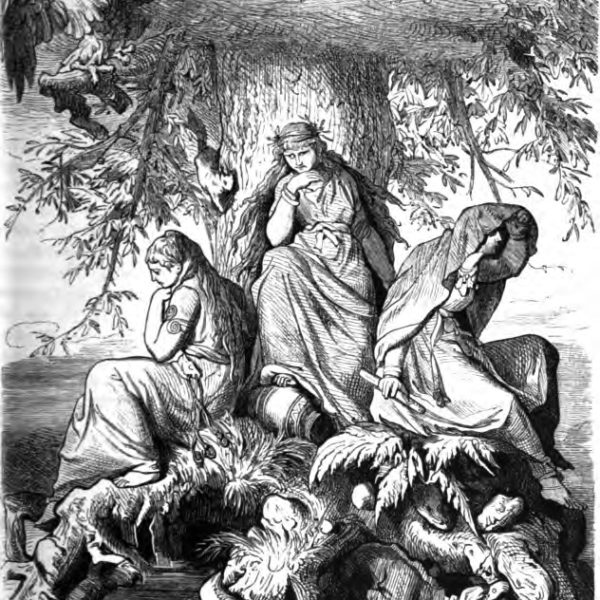

Sacred groves were significant places for the early Norse pagans. At one of these groves near Strängnäs, Sweden, evidence of ritual activity spanning from the 2nd century BCE to the 10th century CE has been recovered. Ritualized deposits include beads, weapons, and bones. In some cases these deposits may have been placed around a particular tree, perhaps representing the world tree.

Like groves, bodies of water were significant places for the ancient pagans. Wooden Iron Age figurines have been recovered in the peat bogs of North Jutland, Denmark. Nearby is a site where Bronze Age discoveries have been made, indicating that the site may have been revered as sacred for a very long time.

Spears, shields, tools, jewelry, coins, and other objects have been found in wetlands, lakes, and rivers throughout Scandinavia. The ritual act of depositing offerings in water is reminiscent of the story of Odin casting his eye into the Well of Mimir to gain divine knowledge.

The Vikings appeared to maintain this practice on their voyages, as Norse ritual offerings have been found in places like Britain.

We can also learn about Viking Era sacred spaces from written records and archeological discoveries in Iceland. When the Scandinavians arrived to this new land during the Age of Settlement (870-930 CE), certain natural sites were identified and designated as areas of sacred importance.

In spite of the rigours of the climate, the place where men sought contact with the supernatural powers was for the most part in the open air. The resorting to holy places was something which could be witnessed by outside observers, often arousing interest and curiosity. Thus in the works of Greek and Latin writers we hear repeatedly of sacred woods and groves, sanctuaries in forest clearings and on hilltops, beside springs and lakes and on islands, and of places set apart for the burial of the noble dead. (H.R. Ellis Davidson, Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1988), p. 13.)

These sacred sites were not often marked by permanent structures, though sometimes simple boundaries such as standing stones or ditches may have been used to demarcate them. Rather, it was the natural features of the landscape itself that were sacred to the Scandinavian pagans who settled in Iceland: the untamed sea, the powerful waterfalls, the dramatic cliffs.

Helgafell—an outcrop of rock on Iceland’s Snæfellsnes Peninsula—is one example of a sacred space used by Norse pagans for religious rituals during the Viking Age.

Thorolf of Mostur, one of the early settlers from Norway, established Helgafell as a place to venerate Thor. He built a small temple here, though we have no surviving description of what this structure may have looked like.

As for why Norse sacred sites were not typically marked by buildings or manmade boundaries:

Tacitus wrote of the Germanic peoples in the first century CE in Germania: ‘The Germans do not think it in keeping with the divine majesty to confine gods within walls or portray them in the likeness of any human countenance. Their holy places are in woods and groves, and they apply the names of deities to that hidden presence which is seen only by the eye of reverence.’ (H.R. Ellis Davidson, Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1988), p. 16.)

That said, Tacitus was not entirely correct; Bronze Age and Iron Age idols of the Germanic gods have in fact been recovered throughout Scandinavia. Yet in comparison to the Romans and Greeks, who created elaborate carvings, paintings, and temples, it’s understandable why Tacitus drew this conclusion.

Additionally, Tacitus died in 120 AD, meaning there were hundreds of years of Norse religious history (including the Viking Age) that occurred after his death and are not accounted for in his writings.

Now let’s consider the types of outdoor ritual spaces we do know about, beginning with the word vé, which is Old Norse for “shrine” or “sacred space.”

This term appears in skaldic poetry as well as in place names. For example, the name of the city Odense, Denmark is derived from Odins Vé, which translates to “Odin’s sanctuary.” This naming indicates a place where open worship may have occurred.

Another example of an outdoor, open worship space is Hove in Trøndelag, Norway. Here, offerings were placed by a row of ten posts bearing images of gods. No trace of a building has been found at this site.

A second important term that appears in Viking Age poetry is hörgr, which refers to a pile of stones where offerings were made. Essentially, a hörgr was an outdoor stone altar.

This term is used several times in the Poetic Edda, such as in the poem Hyndluljóð. In this poem, Freyja praises Óttar for his use of a hörgr to venerate her. Below is the translation by Andy Orchard:

He made me a high altar

of heaped-up stones:

the gathered rocks

have grown all bloody,

and he reddened them again

with the fresh blood of cows;

Ottar has always

had faith in the ásynjur.

Norse Pagan Temples and Indoor Sacred Spaces

Early archeological discoveries indicate that physical boundaries (though not necessarily four walls and a roof) were sometimes erected around sacred spaces, perhaps to separate the area from the mundane world.

The earliest enclosures for sacred spaces appear to have consisted of an earthwork or ditch to mark off the area in which worship or special rites took place. Such enclosures might be square, rectangular or circular in shape, and might contain such features as ritual shafts, springs, hearths, pillars, standing stone or monoliths. (H.R. Ellis Davidson, Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1988), p. 27.)

Bones and other offerings have been found in these simple enclosed spaces, indicating that they served as a place to privately worship and consult with the divine, rather than a place for large assemblies or congregational services. Visitors to these sacred spaces may have viewed shrines and figures of the gods from the other side of a fence, wall, or ditch.

More elaborate religious temples (which are generally referred to using the term hof) have been mentioned in the sagas. Some of the sagas depict these temples as elaborate constructions filled with statues of the mighty gods, but it is important to be mindful of the Christian influence on these depictions.

The most famous Norse temple is the one at Uppsala in Sweden, which was described by Adam of Bremen in 1070 as being “entirely decked out in gold” with great statues of Thor, Odin and Freyr in the center of the hall. Archaeological investigations have revealed postholes, which support these claims of a large temple. However, little else has been recovered.

Now, let’s consider a few of the notable archeological discoveries that can tell us about the temples and halls used by the ancient pagans of Scandinavia for religious rituals:

The most convincing evidence for a pre-Christian sacred site is at Mære on Trondheim Fjord, where an important sanctuary is known to have existed in the Viking Age. The medieval church there originally stood on an island, and traces of earlier buildings were discovered beneath it. The earliest appeared to date back to about AD 500, and was marked by post-holes which held the main pillars of the building. These had signs of burning at the bottom, and a number of tiny pieces of thin gold foil known as goldgubber in Denmark were found. (H.R. Ellis Davidson, Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1988), p. 31.)

The gold foil material recovered at Mære depicts a male and female figure embracing or facing one another, and may be associated with the Vanir deities. At Mære, it is possible these images were meant to hallow the wooden temple and make it sacred.

Since the publishing of Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe in 1988, new discoveries have been made.

In 2000, the remains of what was likely an Iron Age temple were excavated in Uppåkra, Sweden. This ritual building had been rebuilt several times over the span of more than six hundred years, each time as a high-timbered building with a stave-wall structure.

Numerous objects have been recovered in and around the site of the temple. Inside, a bronze and silver beaker, a glass bowl, beads, jewelry, and a total of 111 gold-foil plaques bearing images of figures have been identified. The dating of these objects spans hundreds of years, suggesting a continuous tradition of ritual offerings.

Outside, to the north and south of the building, the ritual deposits are even more impressive: more than 300 objects have been recovered from the excavation site to the north, namely spear heads, shield fragments, and other weaponry. Most of these items appear to have been destroyed and deposited in a similar manner to the famed peat bog finds in Denmark.

Each iteration of the building included three entrances, one facing north and two facing south, and a fireplace in the center of the building. This continuity from the late part of the Pre-Roman Iron Age through the late Viking period makes the building at Uppåkra incredibly unique, and suggests that it served as an important sacred space for the community over the span of several centuries.

In 2020, archeologists unearthed a temple in Norway with a layout that was nearly identical to the building found at Uppåkra. It is believed that the temple was used for performing sacrifices to gods during the midsummer and midwinter solstices. This is the first and only temple of its kind discovered in Norway.

Other archeological discoveries from the last several decades suggest that there may have been two main categories of cultic and religious buildings used during the Late Iron Age in Scandinavia:

- Large temples and temple farms (as proposed by the Danish archaeologist Olaf Olsen) where ritual celebrations, feasts, and sacrifices were held

- Smaller religious buildings that were separated from the festive hall and more specifically used for ritual purposes.

Whether feasting and religious rituals took place in the same building or separate buildings, it is clear that the ritual depositing of jewelry, weapons, vessels, and other items was of great religious importance to the Norse pagans. From the peat bogs of Denmark to the temples of Sweden, we see evidence of this behavior time and time again.

These archeological discoveries indicate that the primary function of pagan temples would have been communal feasts and blóts held by the king or local leaders. During these communal gatherings, ceremonial mead or ale was used to hallow the feasting hall and sacrificial meat was served in a large cauldron.

Gro Steinsland, a historian of Norse paganism, has theorized that whether or not the Norse pagans used temples for rituals and worship was a mater of economics. In the richest areas, elaborate temples were more likely to have been constructed; in poorer communities, blóts were more likely to take place outdoors or in whatever space was available.

Did Norse Pagans Set Up Altars in Their Homes?

We receive a brief answer to this question in the following excerpt:

Individuals in Scandinavia evidently set up small shrines for their own use, as Thorolf of Helgafell is said to have erected a ‘temple’ for Thor near his own house in Iceland, where the sacred ring of the god and bowl for sacrifices were kept. (H.R. Ellis Davidson, Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1988), p. 32.)

But to fully answer this question, it is important to once again return to the key points we have covered throughout this article:

- The Old Norse religion centered around survival, the family unit, and the community

- There was no single doctrine linking all Norse pagan religious practices

- Local land spirits may have been just as important as major deities

- Sacrifices (blóts) and rituals were of key importance to practitioners

- Blóts often took place outdoors, perhaps on stone altars (hörgr) and occasionally inside temples

- Feasts, rituals, and blóts often took place during the same event

- Sacred spaces took on many different forms, from open-air altars and small wooden constructions to large communal temples and temple farms

This is important to remember, because it supports the idea that there was almost certainly no single altar or shrine setup replicated by all Norse pagans in their homes.

Many modern pagan religions place great emphasis on the arrangement and design of the altar; however, during the Viking Age worshippers would have likely created a shrine that served the unique needs of their family or village, if they created such a space in their homes at all.

In spite of occasional encircling walls, it is essential to see the sacred place as something not set apart from the ordinary secular world, but rather as providing a vital centre for the needs of the community and for the maintenance of the kingdom. (H.R. Ellis Davidson, Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1988), p. 35.)

How Can Modern Norse Pagans Create a Historically Accurate Sacred Space?

As modern pagans, nearly everything about our way of life differs from that of the Old Norse pagans: the homes we live in, the jobs we do, the foods we eat, and the ways we interact with our communities. It would therefore make sense that our religious practices and sacred spaces would look different as well, even if they are reconstructed from historical sources.

Additionally, as we have discussed in this series, there was no standardized type of sacred space that was replicated by all Norse pagans; some engaged in community blóts in large temples, others used simple outdoor altars, and others still deposited offerings in wetlands and forests (and perhaps some engaged in all of the above).

So, how can modern Norse pagans develop an authentic religious practice?

It is my belief that we can uphold the spirit of Norse paganism in a modern world by emphasizing action over aesthetics, and by prioritizing the foundation of the religion: blóts.

By performing regular blóts (making sacrifices / giving offerings) for gods, goddesses, ancestors, and land spirits, we are already engaging in an “authentic” practice that honors the foundation of what the Old Norse religion was all about.

The gods created man and the world, the culture heroes completed the Creation, and the history of all these divine and semidivine works is preserved in the myths. By reactualizing sacred history, by imitating the divine behavior, man puts and keeps himself close to the gods—that is, the real and significant. (Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane (New York: Harcourt, Inc., 1957), p. 202.)

Some modern pagans set up beautiful indoor altars, adorned with candles, incense, and idols of the gods; others worship outdoors beneath the sky, with no tools except a simple offering dish. As long as the ritual acts are taking place, who is to say which practice will bring us closer to the gods?

At its core, Norse paganism is not about placing the mead in a certain position on your altar, or collecting idols of all the gods, or using a certain number of candles; it is about renewing and strengthening communication with the supernatural world.

For an excellent step-by-step guide to developing your own hearth cult (home ritual practice) as part of a modern pagan tradition, I recommend The Longship.

That said, I strongly encourage all modern pagans to read as many primary sources as they can get their hands on in order to develop a home practice that feels right to them—just as the Vikings once did.

References:

- H.R. Ellis Davidson, Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1988)

- Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane (New York: Harcourt, Inc., 1957)

- Larsson, L. (2007). The Iron Age ritual building at Uppåkra, southern Sweden. https://www.academia.edu/42449912/The_Iron_Age_ritual_building_at_Uppåkra_southern_Sweden

- Sundqvist, O. (2009). The Question of Ancient Scandinavian Cultic Buildings: with Particular Reference to Old Norse hof. https://journal.fi/temenos/article/download/4578/6774

- Einarsson, B. (2008). Blót Houses in Viking Age Farmstead Cult Practices. https://www.academia.edu/5971504/BLÓT_HOUSES_IN_VIKING_AGE_FARMSTEAD_CULT_PRACTICES

- Jackson Crawford (2018, May 8). Historical Worship of the Norse Gods [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/qv8UVW3mBhw

- The Longship. (n.d.). FAQ. The Longship. https://www.thelongship.net/faq/

Can I please get you to email me this article. I am learning about Viking witches and Norse mythology.v

This is so refreshing! Nice to read an article that putthe emphasis on “what is you and your way with/to the gods?” and not “You have to do this and that”.